Then on the sending system I created a tar gzip command and piped it’s output to nc directing to the IP address of the receiving computer and the same network port. I aborted the copy process and setup nc to listen on a particular port and piped it’s output to a tar gz command that would untar and ungzip the files to the required path. nothing had actually started to be copied! I tried using the cp command from terminal and it was only about a third of the way through the copy process having run overnight. To give you an idea of how effective something like that is the attempted copy operation over an SMB share ran for 5 hours and the Finder was still just calculating the number of files which at that point was well over 500,000 files! i.e. Then on the receiving computer you listen with nc and pipe it’s data to untar and ungzip the files on the receiving end. So the trick is to tar gzip the files and pipe the output (no filename) into nc directing nc to a network port number of choice. Netcat to the rescue! Netcat is a very powerful tool it can open a raw network port and pass data through that port and it can listen for a raw data stream on the other end.

Untar gzip free#

Trouble was, there was not enough free disk space to handle the huge file.

So the solution would be to tar gzip the files into one huge file and then copy that file. Watching a performance graph would show it peaking and falling for every individual file. A normal cp operation is slow because it never gets a chance to increase the network bandwidth as it resets for each individual file.

Untar gzip mac#

Had to copy hundreds of thousands of small files from a Linux server to a Mac over the LAN.

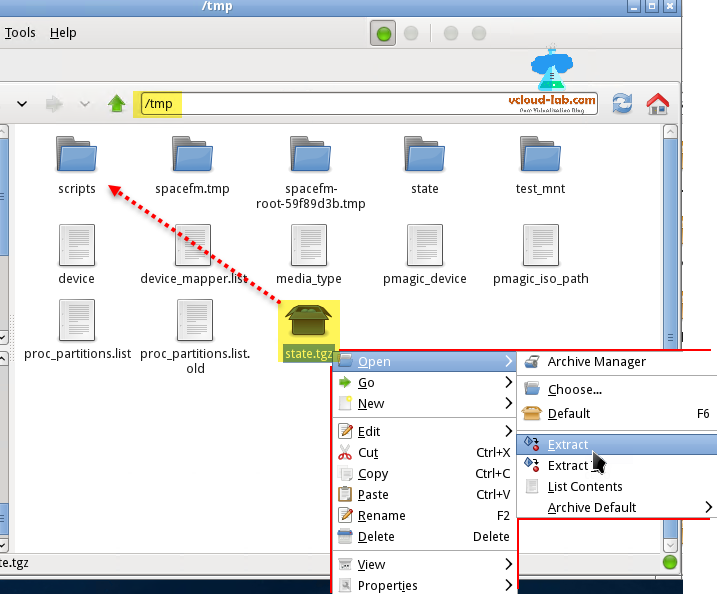

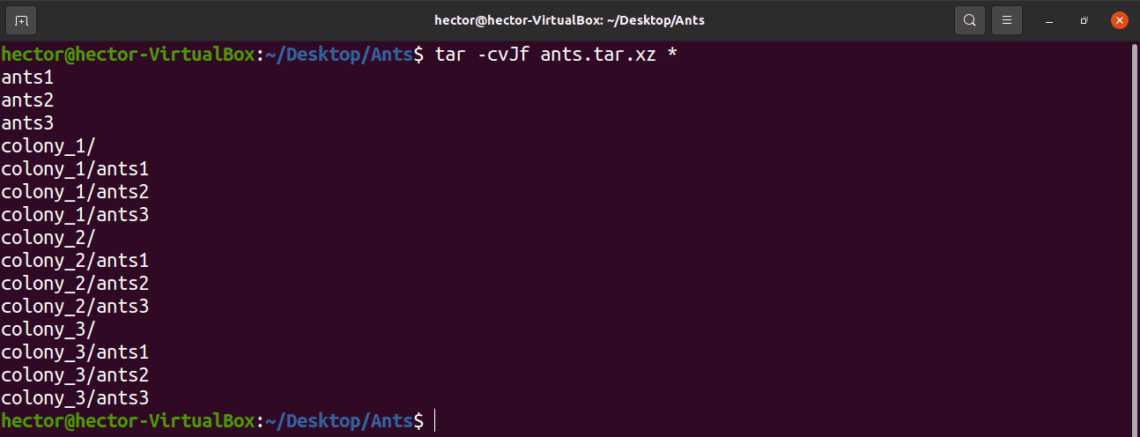

You really want a mind bender, how’s this for fun: and now I just inspired to create my first named pipe for mostly just the fun of it and hey why not I just did my first fsck recovery. Google has indexed and linked me here and though interesting I still think I should consult the man page because I just started picturing doing something with the pipe operator and I am confused on how James /\ sent anything like that without creating a namedpipe, Just baffled right now, and my e2fsck and fsck repair today, brought everything back that I can remember and it seemed more organized all numbered in the lost+found because I am sure I destroyed the file table but seeing as I know the physical layout of my flash, it wasn’t too difficult, now in this sleepy state I say personal buttler tgz directly to another drive without removing the originals or trying to make a local copy first because space is scarce. tgz The trouble for me is creating the tarball in a separate directory without removing the original, and a checksum would be nice too, I just want to make sure everything went ok before I remove the files I want to send. Generally you should untar things into a directory, or the present working directory will be the destination which can get messy quick. Unpacking the gz and tar files can be done with applications like Pacifist or Unarchiver (free), or by going back to the command line with: You can run these as two separate commands if you really want to, but there isn’t much need because the tar command offers the -z flag which lets you automatically gzip the tar file. tar.gz file is actually the product of two different things, tar basically just packages a group of files into a single file bundle but doesn’t offer compression on it’s own, thus to compress the tar you’ll want to add the highly effective gzip compression. jpg extension will be compressed into the file and nothing else. The * is a wildcard here, meaning anything with a. Tar -cvzf itemtocompressįor example, to compress a directories jpg files only, you’d type: From the command line (/Applications/Terminal/), use the following syntax:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)